The idea of cloning a human being has fascinated and unsettled people for decades. Since the birth of Dolly the sheep in 1996—the first mammal cloned from an adult cell—the conversation has shifted from science fiction to scientific possibility. But just because we can do something, does that mean we should?

As cloning technologies quietly advance in labs across the world, we’re forced to confront difficult questions about identity, autonomy, morality, and what it truly means to be human. The science is complex, but the heart of the matter is simple: are we ethically prepared for human cloning?

What Exactly Is Cloning?

Cloning, in biological terms, is the process of creating a genetically identical copy of an organism. It’s not entirely new—nature does it all the time. Identical twins, for instance, are natural clones. But when people talk about cloning in the lab, they usually mean reproductive cloning—deliberately creating a copy of a living being using advanced techniques like somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT).

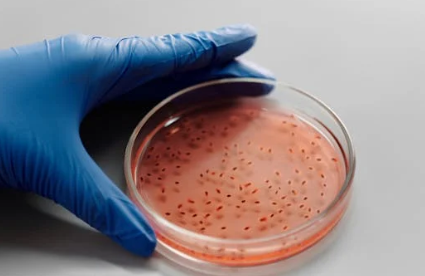

In SCNT, scientists take the nucleus of a cell from the organism to be cloned and insert it into an egg cell that’s had its own nucleus removed. This egg is then stimulated to start dividing like a normal embryo and, theoretically, can be implanted into a womb to develop.

In animals, this has had limited success. Clones are often born with health issues, shorter lifespans, and developmental problems. The process is also incredibly inefficient—hundreds of attempts are often needed to create one viable embryo. And with humans, the stakes—and the risks—are even higher.

The Scientific Roadblock

Even setting aside the ethical dilemmas, the practical hurdles are considerable. Human cloning is still not reliably safe. The high failure rates seen in animals would be ethically unacceptable in people. The idea of creating human lives only to have many fail in the lab raises serious concerns about consent, dignity, and the value of life.

Moreover, cloned embryos and fetuses may be more prone to defects, miscarriages, or early death. Without major breakthroughs in reliability and safety, human cloning remains more theoretical than achievable.

But science is persistent. Techniques improve. With each year, the possibility of someone successfully cloning a human being becomes more real.

The Ethical Landscape

Let’s say, for argument’s sake, that cloning humans becomes technically feasible. No errors. Healthy outcomes. Then the question shifts from “Can we?” to “Should we?”

Here are the main ethical concerns being debated:

1. Identity and Individuality

Would a cloned person be treated as their own individual, or always be compared to the original? This isn’t just a philosophical question—it affects how someone is raised, how they see themselves, and how society views them.

A clone may share DNA with another person, but their personality, experiences, memories, and choices would be their own. Still, the pressure of being seen as someone’s “copy” could impact mental health and self-worth.

2. Parental Motivations and Expectations

If parents clone a lost child, are they trying to replace the original? If someone clones themselves, are they creating a version of themselves to fulfill unmet ambitions? There’s a real risk that cloned individuals could be seen not as autonomous people, but as extensions or replicas—expected to behave or succeed in specific ways.

This challenges the very idea of raising a child with open expectations and freedom to define their own path.

3. Consent and Rights

A cloned person would not be able to consent to their own creation. That’s true for all children, of course, but the situation is more fraught when the intent is to duplicate a particular individual. Does the cloned person have a right to know their origins? Should they be treated any differently under law?

These are not just academic questions—they touch on family law, bioethics, and human rights.

4. Inequality and Access

If cloning ever becomes possible, it won’t be cheap. Which means it may be available only to the wealthy. This raises the risk of further dividing society—where genetic manipulation and cloning could become tools for privilege, not healing.

It also opens the door to more dystopian possibilities: cloning for labor, organ harvesting, or military use. While these may sound far-fetched, history has shown that technology, once developed, often finds uses beyond what was originally imagined.

Arguments in Favor of Cloning

Despite the concerns, some argue that cloning could serve noble purposes:

- Infertility Solutions: For people who can’t conceive through other means, cloning could offer a chance to have a biologically related child.

- Medical Research: Cloning human embryos for stem cell research could lead to better treatments for diseases like Parkinson’s, diabetes, or spinal cord injuries.

- Grief and Loss: Some might find comfort in cloning a loved one who has died, especially if that person was lost young or tragically.

But even these reasons come with caveats. A cloned child is not a perfect copy—memories, relationships, and personalities can’t be duplicated. And using human cloning for grief may risk burdening a new life with the impossible task of replacing someone who’s gone.

Legal and Cultural Lines

In most parts of the world, human reproductive cloning is either banned or heavily restricted. Over 70 countries have formal laws prohibiting it. There’s a broad consensus that society is not ready to handle the consequences—morally, legally, or emotionally.

That said, laws can vary. Some countries have looser regulations or lack clear policies altogether. This creates the potential for what some call “reproductive tourism”—where people go abroad to pursue procedures that are illegal at home.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The cloning debate is not about machines or science fiction—it’s about values, people, and how we define human life.

Even if cloning a person became possible tomorrow, we’d still face more questions than answers. Would cloned individuals be treated with full dignity and rights? Would society see them as equals? Could we resist the temptation to use cloning for control, perfection, or profit?

It’s not enough to ask what cloning can do. We have to ask what kind of world it would create.

Conclusion: Proceeding With Caution

The ethics of cloning aren’t just about the act of making a copy—they’re about how we treat life, how we define identity, and what limits we place on our desire to control nature. Human cloning may never be widespread or accepted, but even the possibility forces us to reflect on deep human truths.

As science inches closer to what once seemed impossible, we must be clear-eyed—not just about what we’re building, but about why we’re building it, and who it’s for.

Are we ready? Perhaps not yet. But it’s time we start having the conversation, honestly and carefully, before the question stops being theoretical.