In an era of sleek glass screens, cloud syncing, and AI everything, it might seem odd—almost regressive—that people are suddenly craving the rattle of a Motorola Razr closing with a satisfying snap or the tactile wheel of an iPod clicking through playlists. Even stranger: they’re proudly showcasing these artifacts online. But beneath the irony lies something deeper. The return of “nostalgia tech” isn’t just a trend—it’s a form of cultural resistance, a search for control, and perhaps, a way to reclaim a digital life that felt smaller, slower, and more personal.

The Aesthetic of Memory

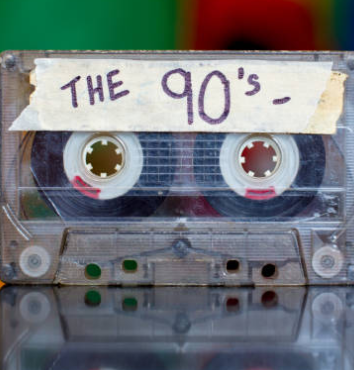

Scroll through TikTok or Reddit forums, and you’ll find a growing subculture obsessed with early-2000s tech. Not just the devices, but the whole atmosphere they evoked: lo-fi ringtones, pixelated webcams, MSN chat windows, MySpace layouts with garish backgrounds and autoplay music. It’s a visual and emotional throwback to a more chaotic but somehow more earnest version of the internet. And it feels like a refuge.

Part of this revival is about look and feel. The aesthetics of old tech—clunky plastic, tactile buttons, neon lights, rounded fonts—stand in contrast to today’s sterile, uniform design. There’s a rawness to the old web. Things didn’t match. Sites weren’t optimized. Navigation was awkward. But it was also human. You had to know how to code a bit to customize your MySpace, or burn a mix CD. That friction created attachment. Today’s tech may be more efficient, but it often feels impersonal, even invisible.

The Rebellion Against Seamlessness

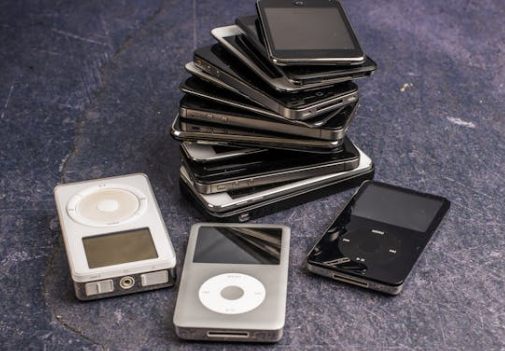

Modern devices aim to erase friction. Everything is faster, smarter, connected. But in that convenience, something else is often lost—attention, intention, and a sense of place. A flip phone doesn’t multitask. An iPod doesn’t ping with notifications. These limitations are now features, not flaws.

By intentionally choosing retro tech, users are carving out digital boundaries. They’re saying: I don’t want my phone to be a surveillance tool, a job site, a dating app, and a camera all in one. I want it to be just a phone. There’s a newfound appreciation for doing one thing at a time—texting when you text, listening when you listen. The multitool has become overwhelming. Simpler devices let people step outside the endless scroll without abandoning connectivity entirely.

Memory as a Safe Haven

There’s also the comfort factor. Nostalgia tech brings people back to a moment before everything became so fast, so public, so optimized for engagement. For many, flip phones were a teenage rite of passage. iPods were the soundtrack to first heartbreaks, long bus rides, summer afternoons. These objects are tied to specific, tactile memories.

But more than just reminiscing, people are reconstructing these pasts in real time—curating their current lives to include analog elements not because they need to, but because it feels good. It’s not just about yearning for a “simpler time,” which may or may not have been simpler. It’s about anchoring oneself amid the noise of now.

The Algorithm-Free Zone

Old devices are not just retro; they’re off-grid. Your iPod doesn’t know your mood. It doesn’t nudge you toward a pre-made playlist. It’s your music, chosen by you. Your flip phone doesn’t track your steps or send behavioral data to third parties. In a world where algorithms decide what we see, buy, and believe, nostalgia tech provides a space where you can still curate without being curated.

Even old web aesthetics—like hand-coded websites, blog rings, pixel fonts—are seeing a rebirth. Platforms like Neocities are helping people make websites from scratch, just for fun. No followers. No metrics. Just digital self-expression, for its own sake.

Not Just a Trend

While some might dismiss this resurgence as a passing fad, its persistence suggests otherwise. Retro tech is popping up in fashion campaigns, music videos, and art installations. Brands are reissuing simplified phones. There’s even a secondary market for original iPods and early digital cameras. These aren’t ironic purchases anymore. They’re part of a broader reevaluation of how much tech is too much.

This is not a wholesale rejection of modern technology, but a recalibration. People aren’t necessarily throwing away their smartphones. Instead, they’re building in quiet zones, analog spaces, and moments of pause. They’re reminding themselves that tech is supposed to serve humans—not the other way around.

Closing the Loop—But Not Too Tightly

The return of nostalgia tech is layered: aesthetic choice, emotional comfort, quiet resistance. It’s not about living in the past, but about asking what was worth carrying forward. As we barrel into the future, sometimes it’s the tools we left behind that help us remember who we were—and who we still want to be.

In the end, maybe the real value of these old devices isn’t in what they do—but in what they don’t.