In the high-impact world of sports, there’s a type of injury that doesn’t leave a visible scar, doesn’t need a cast, and doesn’t always stop the game. Yet, its effects can outlast a broken bone or torn ligament by years—sometimes decades. Concussions, and the broader category of traumatic brain injuries (TBIs), have become one of the most urgent and least understood health issues in athletics.

For a long time, concussions were brushed off as “getting your bell rung.” Players returned to the game minutes later, dazed but determined. Coaches often praised toughness over caution, and leagues lacked clear protocols. But that era is fading. With growing evidence and tragic headlines involving former athletes, the consequences of head trauma can no longer be sidelined.

Still, what remains elusive—sometimes even to the athletes themselves—is the long tail of these injuries. The headaches and foggy thinking might fade in a few days or weeks, but for many, the real impact begins once the stadium lights go out.

A Blow to the Brain, Not Just the Body

A concussion is caused by a bump, blow, or jolt to the head—or even to the body—that causes the brain to move rapidly back and forth inside the skull. That motion can cause chemical changes and damage brain cells. But unlike a visible bruise or sprain, the effects are internal and often delayed.

Common short-term symptoms include dizziness, confusion, memory loss, nausea, and sensitivity to light or noise. But what makes concussions especially dangerous is their unpredictability. Two players may suffer similar hits but recover very differently. And multiple concussions, especially when sustained over time, compound the risk of long-term cognitive decline.

Life After the Final Whistle

It’s the aftermath that concerns researchers, athletes, and families most. In the past two decades, studies have increasingly linked repeated head trauma to serious, often debilitating conditions:

- Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE): This degenerative brain disease, found in individuals with a history of repeated brain trauma, has become a headline issue in American football, hockey, boxing, and even soccer. CTE can lead to memory loss, aggression, depression, and dementia-like symptoms, often years after retirement.

- Mood Disorders and Personality Changes: Athletes with a history of concussions are more likely to experience depression, anxiety, irritability, and difficulty regulating emotions. These changes aren’t always immediate, and can surface gradually, making them harder to link directly to the original injury.

- Cognitive Impairment: Slower reaction times, difficulty concentrating, and poor decision-making skills are common among those with repeated TBIs. For some, even daily tasks like reading, driving, or following conversations become challenging.

- Increased Risk of Neurodegenerative Diseases: Emerging research suggests that head trauma may be associated with an increased risk for Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases later in life.

The Silent Suffering

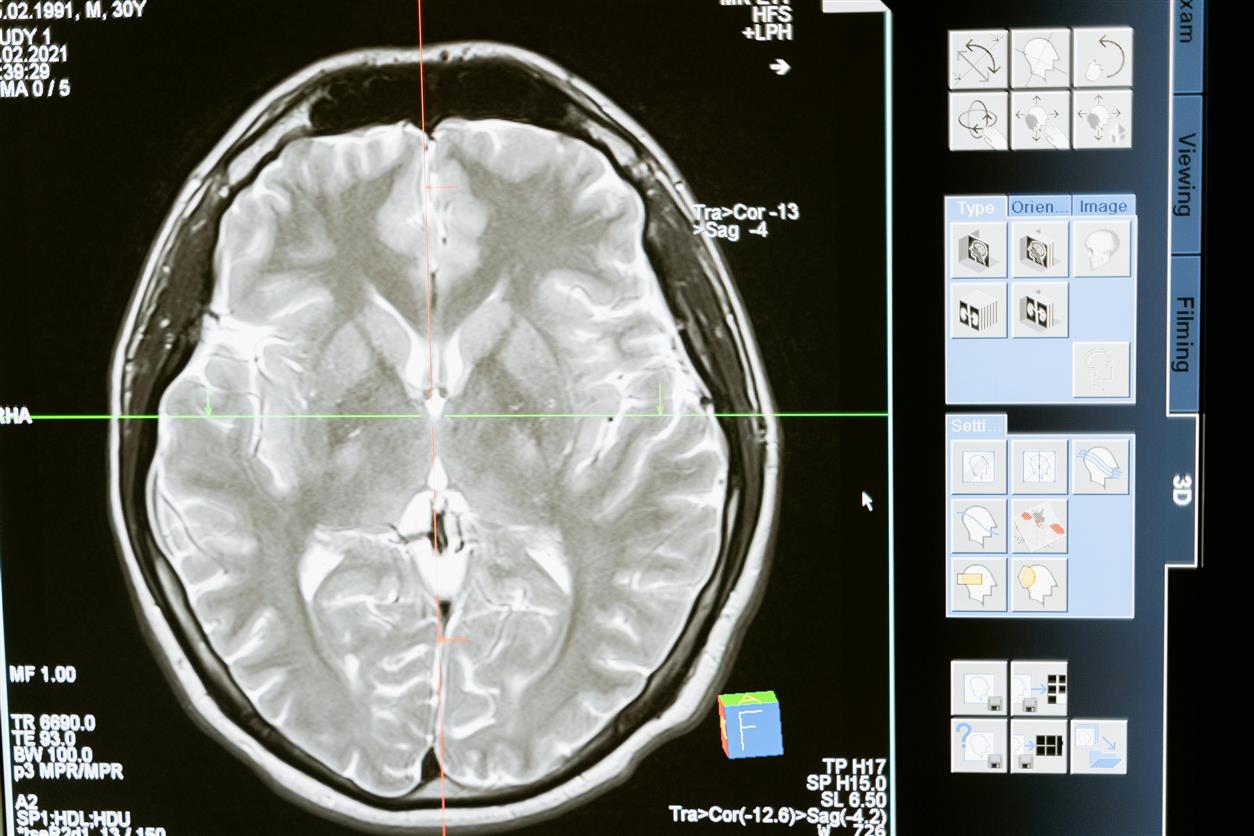

One of the most frustrating aspects of post-concussion syndrome and related conditions is their invisibility. There are no scars. Brain scans don’t always reveal damage. Athletes who look physically fine often struggle in silence, unsure how to articulate what’s wrong—or afraid to admit it.

This is especially true for younger athletes and students, who may experience academic challenges, social withdrawal, and emotional distress without realizing their struggles stem from a past injury. The invisibility can breed isolation and self-doubt.

And in a sports culture that often rewards perseverance and grit, there’s still pressure to downplay or hide symptoms.

The Shifting Landscape of Awareness and Response

Professional leagues have made changes. The NFL, NHL, and other organizations now have concussion protocols requiring players to be evaluated before returning to the game. Helmet technology continues to evolve, and sideline assessments are more frequent.

But critics argue that these steps, while important, are reactive. By the time symptoms show, the damage may already be done. More proactive approaches—such as baseline cognitive testing, limiting contact practices, and even delaying the introduction of tackle football for young children—are gaining traction, though not without pushback.

Colleges and high schools are also facing greater scrutiny. Lawsuits from former athletes, combined with media attention and parental concern, have led to rule changes in many youth sports. Still, implementation is inconsistent, and access to proper medical evaluation can vary widely based on geography, funding, and school resources.

What Can Be Done?

There’s no single fix, but a few priorities have emerged among doctors, trainers, and mental health advocates:

- Education and Transparency: Coaches, players, and parents must recognize that concussions are brain injuries, not just minor setbacks. Early recognition is key, and recovery should be respected.

- Long-Term Monitoring: Medical care shouldn’t stop after symptoms disappear. Continued cognitive check-ins and mental health support are essential, particularly for athletes in high-impact sports or those with a history of head trauma.

- Mental Health Integration: Depression and anxiety are not just side effects—they’re symptoms that demand direct treatment. Integrating mental health professionals into athletic programs is a growing priority.

- Shifting the Narrative: Valorizing players who “shake it off” after a hit reinforces dangerous norms. Teams and leagues must celebrate caution and self-reporting, not stigmatize it.

Redefining Strength

Perhaps the biggest shift must happen in how we define strength. Playing through pain is no longer a badge of honor when that pain risks permanent brain injury. The toughest move an athlete can make might be stepping off the field when their head isn’t right.

It’s time to retire the idea that invisible injuries don’t matter. Because the truth is, concussions don’t disappear when the game ends. They often linger in boardrooms, classrooms, and living rooms long after the crowd has gone home.

And if we’re serious about protecting athletes, the work doesn’t end with better helmets or updated protocols. It starts with changing how we see the brain—and how we value the long game over the next play.